At around 3:30 p.m. on February 5, 1924, the most devastating mining disaster in Minnesota history happened at the Milford Mine near Crosby. The first shaft was sunk in 1917. By 1924, the mine reached depths of 200 feet under the ownership of George H. Crosby. Milford Mine was producing rich deposits of manganese ore and shipping around 70,000 tons per year.

The mine was located between Wolford Lake (now Island Lake) and Foley Lake (now Milford Lake) near Wolford. In the 1920s, the richest deposits of manganese were located near the mine’s property line, just feet away from the shore of Foley Lake. In February 1924, most of the work to remove the rich manganese was done at the 165- to 175-foot level.

On the day of the disaster, 48 men were working below ground. Just 15 minutes before the end of their shift, a blast of wind blew through the mine, blowing out their lamps. The strange sound of thick liquid falling came next as many miners struggled to relight their lamps. In the few seconds it took them to realize what was happening, several men were already unable to move due to the thick mud pouring into the tunnels. Those who were able ran for the exit as lake water quickly filled the mine. Unfortunately, many of the miners running for their lives were overtaken as the water reached the top of the tunnel. Only seven men made it to the surface.

The last three men out of the mine recalled feeling the wind and seeing water flowing into their working area. They ran, often stumbling, towards the only shaft to the surface with the water reaching their ankles and then their knees. Finally, exhausted, they reached the wooden ladders that would bring them up 175-feet to the surface. When they were pulled out, the water was just 10 feet from the top of the mine. The last miner out reported feeling the water at his chest as he climbed.

A surface cave displaced mud between Foley Lake and the mine causing mud to flow into the mine, soon followed by lake water. Whistles and sirens from nearby mines and towns wailed for more than an hour to alert residents and summon help. Sadly, 41 men were trapped in the mine. When rescue teams arrived and saw the water lapping just 10 feet below the surface, they knew there was no chance for anyone else to be pulled from the mine alive. It took less than 20 minutes for 38 women to become widows and 80 children to be left fatherless.

Recovery efforts were slow and dangerous. First, water from Foley Lake was pumped into the Mississippi River, then the mine was drained. Thick mud and debris blocked the tunnels, and rescuers were concerned that moving the mud would trigger additional cave-ins. Crosby considered sealing the mine with the 41 bodies left underground, but the widows banded together and demanded he recover the remains of their husbands. The effort took nine months to complete.

A commission in charge of looking into the disaster found no fault and no liability for the mine owners. The mine reopened in 1925 and operated until 1932. After the mine closed, the town emptied as residents moved to nearby Wolford, Cuyuna, Crosby, or other mining towns that dotted the area. It didn’t take long for the site of the mine to crumble and be reclaimed by nature.

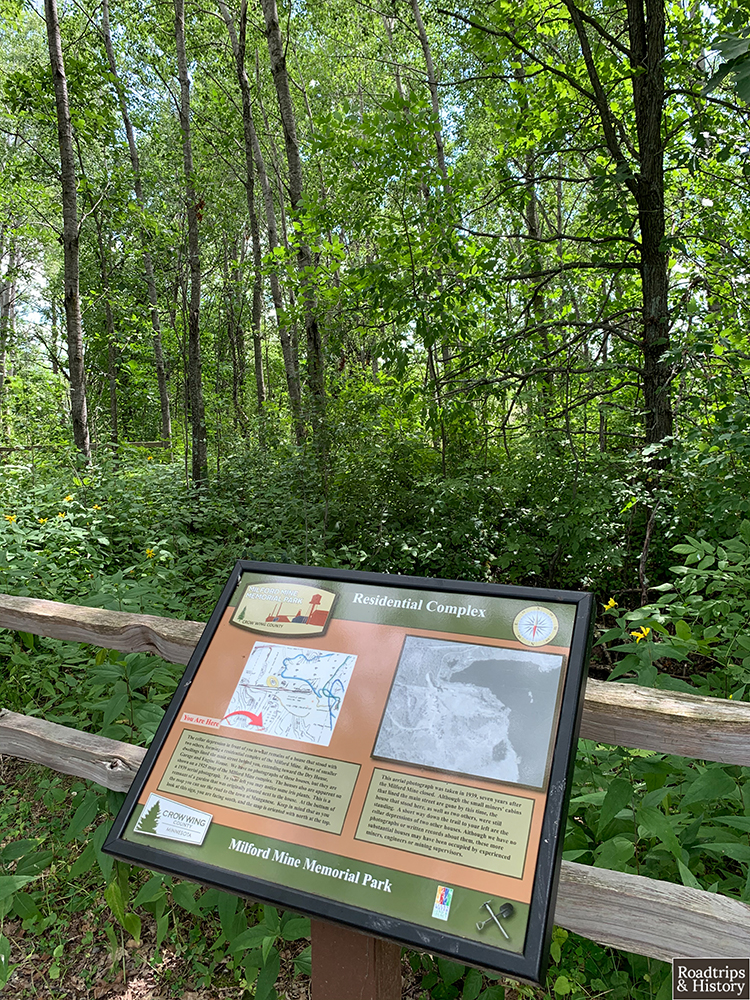

Today, a memorial park covers the site of the old mine. I was able to hike through the remnants of the mining operation and view the townsite. It’s possible to fish, canoe, and swim in the lake that once poured into the Milford Mine. Interpretive signs tell the story of the mine and the people who worked there. But most importantly, the 41 people who lost their lives in the disaster are memorialized throughout the park. The names of both victims and survivors are placed on slats of the bridge visitors use to access the old mine site.